Math dept. adopts new textbooks

Changes in delivery system cause concerns among students, parents

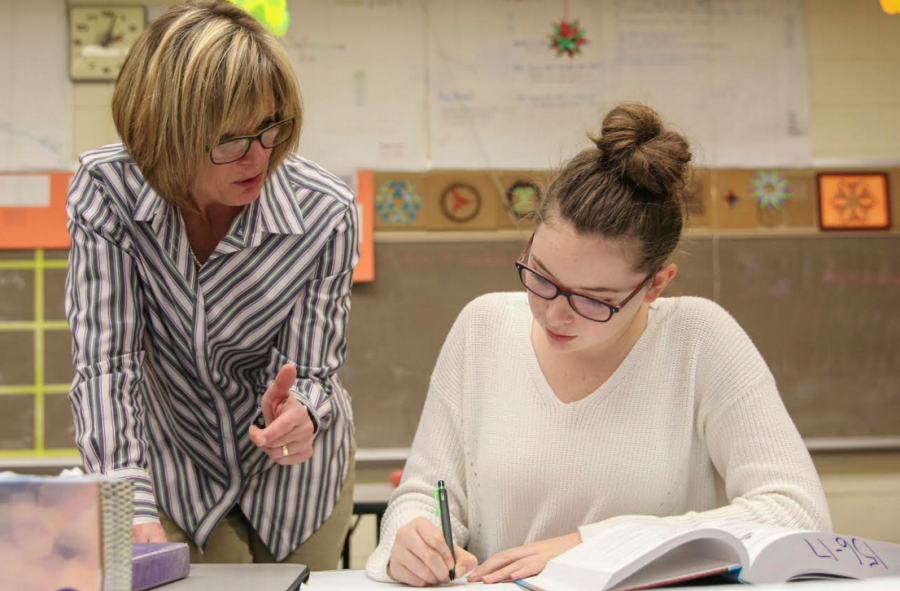

Photo by: Maddy Emerson

On Sept. 27, a parent meeting was held to explain the new math delivery system. With only 24 hours notice, over 90 parents and students attended what was supposed to be a 30 minute meeting, but turned into an hour and a half. Parents voiced concerns about the effectiveness of the new instructional method, which was set into motion by a new textbook adoption. Principal Phil Bressler and members of the math department fielded questions about the new delivery system and implementation of group learning.

Over a month after the meeting, questions remain unanswered about the effectiveness of the delivery system and how students’ progress will be monitored.

During the spring of 2017, the math department considered various math materials before deciding on the College Preparatory Math (CPM) program. The teachers instituted a new class format in which students work in groups to complete daily assignments. To the students, the change seemed to be a complete overhaul of the system.

“Obviously, any curricular change is going to have some hiccups and is going to be stressful and hard to adjust, but

because my grade is dropping,” junior Carter Uttley, an algebra II student, said.

According to math teacher Rhonda Willis, the change is not curricular, but is instead a new way of learning and teaching.

“The curriculum is the same. What’s different now is, instead of just feeding information to students and expecting them to mimic what they’re seeing us do, we’re helping guide them through more of a discovery process,” Willis said.

Bressler finds the new system to be a step toward higher level learning since it teaches students to think deeper and share their results with the group.

“The traditional delivery system has been direct instruction. The problem they had was they don’t understand why,” Bressler said. “We’re trying to get kids to think more mathematically instead of just being a calculator. The students [who] have always been at the top, now instead of the reasoning why they did it staying inside their own head are now being shared with classmates who might struggle.”

Holly Kent, a parent of sophomore Carmen Kent, who is enrolled in algebra II, attended the parent meeting. One concern she has is about the emphasis on group learning.

“My daughter has grown frustrated that her group is often not engaged in discussions to find answers to problems or concepts in the material,” Holly said. “Her experience is that most of the time group members have difficulty staying on task. She feels like the responsibility then falls on her to complete the lesson and make sure the rest of the group understands the material.”

Willis believes group learning can be beneficial to everyone.

“Statistically, this is the right way to learn whether you are a high student or a low student,” Willis said. “Research shows that working collaboratively helps everyone. Some students don’t like it, but it will help them and we’ll work with them and try to make sure every student is where they need to be.”

However, Wayne Bishop, a math professor at California State University in Los Angeles, disagrees. Bishop was a member of the 1999 and 2001 state adoption content review panels in California. CPM ultimately withdrew its application to be considered as a curriculum, but not before Bishop evaluated it.

“Being told wrongly by a convincing fellow student, a situation common in un-led team settings, is far worse than being told what is correct by a competent teacher,” Bishop stated in his findings.

Junior Leah Wescott, who is in algebra II, feels she is struggling.

“My group has kind of got to the point where we can’t ask questions at all,” Wescott said. “We try to figure it out, but we kind of just sit there pretty much the whole class period.”

Uttley shares Wescott’s complications in algebra II.

“Right now, it’s so one-sided with the instruction and the actual teaching. The teachers are doing what they’re supposed to do, I’m not holding it against them, but what they’re supposed to do is not enough for those of us who have been taught through repetition our whole lives,” Uttley said. “We don’t have the capabilities, and we’re not use to teaching ourselves all this math without any instruction. It’s super one-sided and the teachers aren’t teaching.”

In the standard CPM program, teachers are “facilitators” who monitor class discussion, pose purposeful questions and promote productive struggle instead of standing at the front of the room lecturing. But according to Willis, the department has recently altered the structure.

“If you were going to teach the way CPM says, the teacher would be a facilitator. That is not the way we are doing it because we know we need a more active role in the classroom,” Willis said. “The way CPM would train us is let the students struggle through. As teachers here at PHS, we are far more active than what a typical, trained CPM person would probably be.”

As teachers are combining more of the traditional system with CPM, sophomore algebra II student Sophia Pinamonti is noticing a difference.

“Now we’re getting worksheets and do them as a team, but then we’re going over them with the whole class, so that’s better because [the teacher] works with us after we do it,” Sophia said. “Last chapter, I feel like we did do good on the test because we figured out what we needed to do. This chapter, we’re getting a graphic organizer to work them out in, so that’s helped.”

The process of picking a new textbook required the math department to research different textbooks and styles. The new textbooks only include homework problems where the old textbooks had examples of how to work the problem. Now, those examples are online at www.cpm.org.

“We didn’t have very many [textbooks] to choose from because there weren’t many that met our expectations. Most books are very traditional, and the thing is, if you look at our scores compared to national and international, we’re not where we need to be. Something needs to change,” Willis said. “This is what’s being discussed at the state level. If we aren’t willing to make those changes, then somebody is going to make those changes for us and it won’t be math people doing it. Change is going to come, so why not be the ones choosing the change.”

Math teacher Trevor Elliott believes CPM offers the students a deeper level of learning.

“The benefits that were discussed when the new textbook series was chosen were the changing standards and test applications that are moving towards more situational based questions and deeper thinking that is emphasized at the state and national level,” Elliott said. “Students have to focus on the principled knowledge, which is the understanding of the concepts and ideas, instead of on only the procedural knowledge, which is simply steps. Understanding the concepts and ideas can allow for applied learning and higher retention of material to be used in the next class.”

One of the main concerns with a new system is the question of how it will be monitored. Though CPM has only been implemented for three months, students’ progress will eventually be observed through Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) testing and ACT scores.

After personally conducting research, Holly’s worries were not alleviated.

“This program has been around for 25 years and has been highly controversial,” Holly said. “It is by no means is a ‘new’ way of teaching and there is empirical evidence available that would suggest that CPM may actually be detrimental to student success.”

In addition to MAP and ACT, formative and summative assessments in the form of tests and quizzes are currently being used.

“Well, it’s still early. Now, we are evaluating a lot of it from observation,” Willis said. “We will have MAP scores over time. We’ll have state assessments to look at and ACT scores to look at. Granted, that takes some time, but it takes time to evaluate a program. It’s not immediate.”

Previously this semester, Uttley did not feel that students were able to reach their full potential in working with CPM.

“I don’t even feel like I have a math class. I go into class to sit there and do my work. I do everything I’m asked to do, but what I’m asked to do is definitely not contributing to class learning,” Uttley said. “There is definitely light in CPM, but the execution right now is where it’s going to be for the whole year. I don’t think there’s any farther it can go this year without more training with the teachers or drastic changes in the program. Right now I think it’s at the level it’s going to continue to be at, which is unacceptable.”

Willis believes students will be able to overcome these challenges and will see improvement in the future.

“[CPM] teaches students to think and not just watch and copy. How can that be wrong? It teaches them how to think deeply about mathematics, to communicate with each other, and they’re learning math in the process. We are not hurting any students. We would never ever jeopardize a student’s education to try something new,” Willis said. “This is a lot of work. I’ve never worked this hard. And we absolutely wouldn’t be spending the time if we weren’t confident this was the best thing for kids.”

Elliott has seen his students progress this year by learning real-world skills during class.

“The conversations that students are having within the groups about the material and their ability to work together to accomplish a task that may cause some struggle is a definite positive,” Elliott said. “Having the ability to work together with their peers allows students to acquire soft skills that will be beneficial outside of the school setting.”

Wescott also researched CPM once she heard it would be implemented in her math class.

“I did a bunch of research on it and it said it brings down 20 percent of ACT scores in math and every program that has started it has taken it away the next year because of how bad it has worked out,” Wescott said. “The state that started it, ended it because of how bad it was.”

Dr. James Tenbusch, a previous superintendent in Illinois for over 15 years, conducted a three-year survey with Zion-Benton High School in Zion, Illinois, using the Educational Planning and Assessment System (EPAS). EPAS, which is a linked series of three tests, is designed to measure a student’s educational progress and college readiness.

Zion-Benton High School used CPM for three years before it was discontinued.

“Results showed that the gap between means student performance on EPAS System mathematics aptitude tests and associated college readiness cut scores doubled during the first year of exposure to the CPM curriculum, and quadrupled during the second year,” Tenbusch stated in his findings. “CPM student readiness for a college mathematics curriculum was observed to decrease by approximately 10 percent per year.”

One of the reasons CPM was chosen was because of the math department’s belief of possibility for ACT scores to increase.

“There’s absolutely no way an ACT score could not be helped if you are teaching students to think more deeply and how to understand math more deeply,” Willis said. “I think we have been doing our students a disservice because you go take the ACT and few questions are like what we’ve shown you, they [require] more thinking. With the ACT, they take that basic skill and work it into a strangely worded situation or a weird situation, and we have not taught students how to work through that. But now, we are teaching them to think through that, so I would anticipate them going up.”

Willis encourages parents and students to have trust.

“We were very intentional about truly wanting to do what’s best for kids. We knew it wouldn’t be easy, but we are 100 percent committed to trying to be the best teachers we can be,” Willis said. “We are teaching hard, but we need students and parents to work with us. We would never do anything to inhibit a student’s education, and I just hope people believe that.”

Willis strongly believes in the new delivery system.

“I think the concerns we have is not a curriculum concern. I think that CPM was easy to blame, even if there were some low test scores because I still have some students who score low. What they score low on is not what we’re doing in class. What we’re doing with CPM is working. They’re doing well on that part. The reason they are not doing well on the review [problems] is because they’re not doing their homework. Those who are participating in class are picking up on what we’re doing, it’s good. It’s working, but we just have a large population of students who aren’t doing their homework, so those skills that they were missing, they’re still missing. Some students need to really step it up and make sure they know how to do the homework and they do the homework piece.”

The Booster Redux contacted other members of the math department, but they declined to comment.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Pittsburg High School - KS. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.