Your donation will support the student journalists of Pittsburg High School - KS. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Illustration by: Lane Phifer and Jorge Leyva

Fostering a life

Price tells the story of his two years in the Kansas foster care system, where he spent time at a group home, psychiatric residential treatment facility, contracting office and more.

April 29, 2019

For 28 days, senior Dacota Storm Price’s home was the small visitors room of a KVC Kansas foster care office in Pittsburg.

Price’s time in the office would follow the same routine. During the day, he would eat the Hot Pockets or chicken nuggets the workers heated up for him for breakfast, lunch and dinner. During the night, he would sleep with his feet hanging off of an air mattress.

A KVC worker would check in on him eight times a day and take him to shower at Pittsburg State University (PSU) twice a week. When the office workers needed the room for a visit, they’d temporarily move him into a cubicle. The rest of the time, he spent sitting, wondering about his future.

“Knowing that nobody really wants you, it’s kind of… gut-wrenching,” said Price, who was first placed in care at 15. “Me, I have a lot of thoughts running through my head, so I’m just like, ‘Well, is somebody ever going to come get me? Am I going to be accepted? If I do, what are they going to be like?’ It’s just a bunch of questions just ran through my head that time. A lot of anxiety: a lot of turmoil.”

Price wasn’t the only child spending nights in the office, waiting on the foster care contracting agency to transfer him to a new placement. He heard kids come in and out; they slept in the conference room next to him.

KVC, the lead foster care contracting agency on the Eastern half of Kansas, has come under fire for allowing foster children to sleep in offices. In September of last year, The Kansas City Star broke the story of a foster teen who reported she was sexually assaulted inside a child welfare office. According to The Star’s coverage, in September of 2017, private foster care contractors reported that children had stayed overnight in their offices more than 100 times in the past year, and in April of 2018, dozens still did.

According to Sherry Briggs, a foster care permanency supervisor at KVC, it’s been about a year since any kids have had to spend the night in Pittsburg’s KVC offices.

“I would say at that time, there was just not enough,” Briggs said. “Some of it was circumstances of the children and some of it was not enough resources, or places for children to go. We have come up with more recent resources — more homes, more foster homes.”

Price’s stay in the office was after three moves. He moved after his first foster dad, who he lived with for seven months, lost his foster care license when Price and his foster brothers hotlined DCF to complain about his abusive behavior. He later lived in a group home in Topeka and ran away from the psychiatric treatment facility KVC had placed him in.

According to the Kansas Department for Children and Families (DCF) Kansas Child Welfare Factsheet, the average length of stay for a child who ages out of foster care was 37 months as of June 30, 2017. Ever since he first entered the foster care system in 2016, moving placements became a new norm for Price.

“It’s bad when you can say you’re used to it,” Price said. “I don’t really think about [moving] anymore. I’m just like, ‘Oh, I’m moving, that’s happening again, okay. Where am I going to this time?’ I don’t get my hopes up too high anymore because I always get them brought down.”

The Child Welfare Information Agency defines foster care, also known as out-of-home care, as a “temporary service provided by states for children who cannot live with their families.”

A child can be placed in foster care for multiple reasons, including abuse, neglect, illness and more. In Kansas, DCF determines and investigates whether a child should be placed in foster care.

When DCF separates the child from their family, the organization assigns him or her to a foster care contracting agency, which determines the child’s placement. KVC, the agency Price was assigned to, typically supervises children on the Eastern half of Kansas.

The most common outcome of foster care, according to KVC, is to “safely reunite” youth with their families “as soon as possible.”

However, according to the most recent Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System report, on Sept. 30, 2017, of the 442,995 children in foster care, only 56% had a case goal of reunifying with their parent(s) or primary caretaker(s). Other goals included emancipation, adoption, guardianship and more.

Price joins 4% of foster care children in having a case goal of emancipation.

“When I turn 18, there is nothing in this world that’s going to keep me in that care because when I turn 18, I have all the right to walk out of that court office out of foster care,” Price said.

According to DCF, last month there were 3,922 kids in family foster homes in Kansas and 7,445 total kids in care. A foster family home can only license for up to four foster children.

“We have more foster kids coming in than we do have foster homes,” said Morgan Woods, a foster care worker at TFI Family Services. “That’s why all of our agencies are getting the word out about foster care. It’s difficult right now to keep kids in their home county due to a lack of homes.”

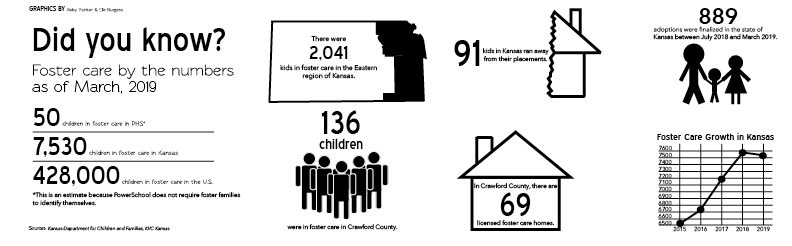

In Crawford County alone, there were 136 kids in foster care on March 31, according to DCF.

Counselor Stef Loveland, a frequent speaker at adoption and foster care conferences, works individually with students in foster care and their foster families. According to her, the growing amount of children in foster care makes the system more complex to manage.

“It’s a beautiful thought in its origin,” Loveland said. “I want to be positive about that, but the reality is there are so many children in this system that it is very difficult to give every child what they deserve and what their families deserve.”

Because KVC couldn’t find Price a foster home in his home county, they placed him into a group home in Topeka instead. Instead of foster parents, the home had a supervising staff.

“I had no problem with that placement,” Price said. “The only reason why I was so frustrated is because I didn’t understand any of the things that were happening before [my first foster dad] and I was still, I guess, going through that and all the case workers. I was angry. I was frustrated. I didn’t know how to properly let it out. I was never taught.”

One day, Price could no longer hold his frustration in. He kicked the wall in his room, and left a hole in it. After the workers found out, he was transported to a juvenile detention center (JDC) and later to a psychiatric residential treatment facility (PRTF).

Price would later run away from the PRTF with one of the patients he met there. For six weeks, they were out on the streets — homeless.

Halfway through his second month, Price turned himself into the police.

“KVC had said I was depressed and I needed help,” Price said. “I didn’t feel any depression. I had told them, ‘Hey, I’m not depressed, I really don’t need this.’ They were just like, ‘Hey, you have no choice in the matter.’ It was stressful. It was a struggle to make ends meet to survive. Most of the time, I was hungry and cold.’”

According to DCF, 91 of the 7,445 children in foster care in Kansas ran away from their placement last month, while 80 lived in independent living homes.

After sleeping in the KVC’s visitors office for 28 days, KVC placed Price into an independent living home, where he had his own apartment, kitchen and roommate.

He was taken out of the home after he violated regulations. After staying in a JDC for a month, he stayed in a temporary foster home for three nights, until KVC found a family for him.

Currently, Price is living in a foster family home with a foster dad. His final court hearing is on July 18, when he has the choice to be emancipated.

Along with moving towns over the past two years, Price also moved schools.

According to Loveland, the normal amount of credits required to graduate at PHS is 26. For a student in foster care, it’s 21.

“That honors the process of if a student needs to move and it’s out of their control and maybe loses credits based on things that happen that were outside of their control,” Loveland said. “This has been put into place to help with that piece.”

Because he only has 14 credits due to online schooling, Price will graduate after completing summer school. After being emancipated, he plans on taking a gap semester and then attending PSU. As a result of his participation in the Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs (GEAR UP) — a federally funded college access program designed to help students in foster care prepare for post-secondary education — the state of Kansas will pay for his tuition.

When he reflects on his two years in the foster care system, Price recalls the lack of stability.

“I would never wish foster care on my worst enemy, like I don’t care if me and this person have been through hellfire, because it’s so unstable,” Price said. “You’re so all over the place. You might expect to have some stable environment where you can finally relax and settle down, but no, you have to be on your toes all the time. There’s so much instability. It’s so stressful.”

Loveland believes foster care in Kansas is a systemic problem. Despite all of its challenges, she says the people involved in its workings are not at fault.

“I guess I view it personally as a system failing, but I still believe in the people that are doing this,” Loveland said. “I believe in these caseworkers. I believe in these therapists. I believe in the after-care managers, like I believe in the organization. I believe in the foster families. They have my utmost respect and honor. It is a system that I believe is flawed — not the people.”

Inspiring change at a local level

The Nickelsons run a Police Protective Custody (PPC) Home and Fostering Connections, a nonprofit organization to help foster children and families.

Photo by: Contributed image

Lacy Nickelson, founder and president of Fostering Connections, sits beside her husband Tom, weights teacher at PHS and co-founder of Fostering Connections. The Nickelsons founded the organization to help both foster children and foster families.

When Lacy and Tom Nickelson decided to open their home to children two and a half years ago, they realized the need for more people to get involved in the foster care system.

Different from a normal foster family, the Nickelsons are a Police Protective Custody (PPC) Care Home. They take in children on short notice who have been placed in police protective custody. This gives the child a safe place to go until he or she is able to get assigned to a long-term family.

“[Becoming a PPC home] opened our eyes to the great need, right here in Crawford County, for quality foster homes,” Lacy said. “And it opened our eyes to the need to support the families that are in it for the right reasons.”

That realization then led the Nickelsons to start an organization called Fostering Connections. It is a nonprofit organization that helps to “benefit both the foster families and the foster children in our area.”

Fostering Connections helps foster children and families through mentoring and free events such as moms’ coffees and kids’ night outs.

“[At moms’ coffees] moms are able to come and once a month meet and receive some word of encouragement, training, prayer and just be around other moms that are like-minded and have shared in the same struggles,” Lacy said.

Fostering Connections’s latest initiative is its VIP kids box program. The organization, as well as community members, put together small boxes with essentials and extras such as socks and toys.

“When kids come into care, many of them are just having to wait for hours before they’re placed with a foster family,” Lacy said. “While they’re waiting, we want them to be able to have something to entertain them or comfort them because the first couple of hours are very traumatic, regardless of age.”

According to Lacy, an issue within foster care is the workload social workers face, with some workers balancing up to 60 cases in a day.

“It’s just a very high stress, high demand [job with] not enough time and many, many cases,” Lacy said. “So many are just doing the best they can, but they just don’t have enough time or energy.”

Because of Fostering Connections, the Nickelsons have been able to witness a number of kids’ lives changed for the better by being in foster care.

“I’ve seen so many that are now finishing up their master’s degree or they’re finishing up their doctorate,” Lacy said. “That’s inspirational to me. I think that foster families could change the trajectory of a child’s life just by being there for them during a rough time.”